Although of Course You End Up Pretending to Be Someone Else

I went to see End of the Tour last night with my brother. I know a lot of you guys were swearing some kind of fatwa against the film, I guess for daring to depict the Patron Saint of White GenX Writer Dudes, David Foster Wallace, but ultimately I decided that I was curious and I fundamentally didn’t give a shit about that stuff. Maybe it’s because I didn’t come to be a DFW fan — if you could call me that — until after he died, but I don’t have an attachment to the guy that makes me respond viscerally in that way to the idea of Jason Segel putting on a bandana and pretending to be him. It might also be that by the time he died, it was 2008, and even if I had been into him I don’t think I would have felt his death on a gut-punch level, mostly because I was 28 by then and hadn’t felt anything in that way since the night they found Kurt Cobain’s body 14 years earlier. And maybe it’s just that I don’t believe in authenticity, so I don’t find it possible for DFW’s to be violated by a graven image. I don’t know, this is coming off as snotty. Maybe I’m just a contrarian. It’s probably that.

Anyhoozy, I was curious to see how completely the movie would commit to the conceit of the book upon which it is based. Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself (a much better title, by the way, than End of the Tour) consists of a brief introduction by David Lipsky, who is listed as the author and is played by Jesse Eisenberg with his usual intense nervousness in the film, and then 200-odd pages of transcripts of a 5-day-long interview-cum-car-trip that Lipsky took with DFW towards the end of DFW’s Infinite Jest book tour. It’s an interesting book, but claustrophobic, because it’s about two profoundly neurotic people negotiating a social interaction, mediated by a tape recorder, in an enclosed space. I actually thought that this had the potential to make for a really interesting movie, if the filmmakers had the balls to overcome their famous subject and the movie-star pedigrees of their actors.

They almost pull it off. The film is basically a low-key take on an old genre long since gone to seed, the road picture, and there are really only two characters with personalities, DFW (Segal) and Lipsky (Eisenberg). They talk, and talk, and talk, and talk, and then they eat, and then they talk some more. Ideas are kicked around, emotions bruited and then retracted, and on the whole Segal really bursts out of the comedy-doofus, live-action-Muppet persona that has made him rich and famous, playing Wallace as reserved and funny and moody and physically intimidating. (Eisenberg, by contrast, basically just Eisenbergs. You’ve seen this performance, or a version of it, in Adventureland and The Facebook Movie. Don’t get me wrong, it’s effective, but it’s nothing new.) A frigid midwest winter landscape scrolls behind them as they drive, walk, eat, talk, fly, and generally try to figure out how much they like each other, how much they’re allowed to like each other, how much they’re supposed to like each other, and whether it’s okay if they maybe don’t really like each other all that much. A lot is made of Lipsky’s envy of Wallace, which I suppose is an accurate reading of the way Lipsky portrays himself in the book.*

*I know a lot of people who loathe book-Lipsky, but I actually think it was fairly brave of him to be totally up-front about the small, ugly feelings he was having all through the experience.

Inasmuch as the movie fails, it fails because it doesn’t have the courage to just let the conversation be the movie. There are various attempts to wedge a narrative into the movie: is Lipsky going to ask Wallace about whether or not he was a heroin addict? Is Lipsky going to mess up DFW’s sobriety by drinking in front of him? Is DFW going to lose his shit when it’s clear that his ex-girlfriend is kind of into this nebbish reporter who is following him around? I heard an interview with Lipsky in which he claims the love-triangle thing actually kinda-sorta happened, but the movie spends much too much time on it, and doesn’t really have the daring to let the viewer wonder whether or not DFW is totally off his rocker: in the movie, it’s clear that Lipsky is hitting on DFW’s ex, in a way that would be fairly innocuous if not for the fact that the character knows the girlfriend has history with DFW, who is literally always in the room as it goes on. This sequence doesn’t sink the film by any means — at least a hint of it is necessary to understand the dynamic between Lipsky & DFW in the film’s second half — but it drags, and feels a little bit ham-fisted.

More egregious is a framing device, in which an older Lipsky (Eisenberg in a bad wig) hears of DFW’s death and is moved to listen to the old tapes of the interview and write the book. It’s cheap, and fairly poorly-written, and mostly just feels hammy and unneccessary. I guess the spectre of DFW’s suicide hangs over everything ever written or said about or by him, and the movie probably shouldn’t assume that (A) everybody knows what happened or (B) people will understand that context years in the future, when they may be watching the film clean. I don’t have a suggestion for how to do it better, other than maybe to give Eisenberg a better wig and not show him openly weeping at a reading at the movie’s end, which feels manipulative and dishonest.

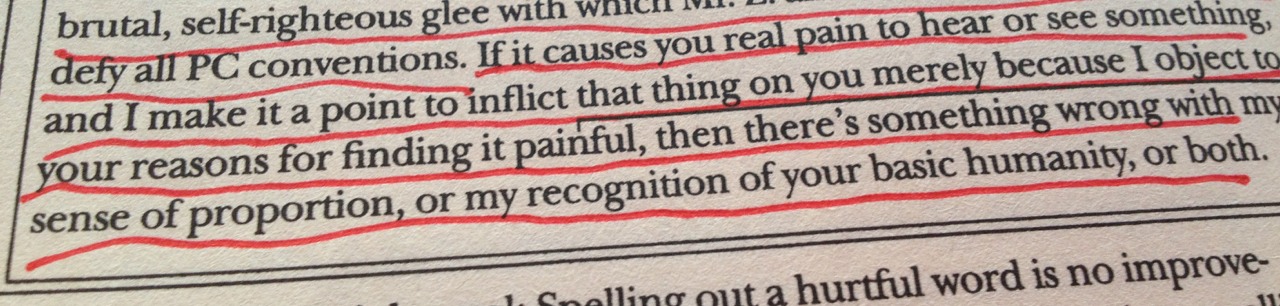

In the end, the movie was pretty good, and its strongest passages all consist of simple conversation between its two principle characters. I do think that the film — like a lot of the people that I know — is a little over-invested in the idea of Wallace-as-saint, leading to some overly-safe choices. In addition to making Lipsky’s designs on DFW’s ex a little too transparent, there’s also slo-mo passage of Segel, still dressed as a photograph of DFW from 1996, dancing alone-but-in-a-crowd at a church, after a kinda funny monologue about how he likes to do the electric slide. This is DFW the angel, the otherworldly agent of good who has seen through the cyicism and irony and pierced to the sincere, authentic heart of life, and it strikes me as basically bullshit, meaning reverse-engineered from the fact that DFW was a small-town, small-c conservative who also happened to have addiction issues and mental health problems. DFW spends the entirety of Lipsky’s book, and the movie based on it, anxious about the portrait that would be painted of him once the interview was over — worried that Lipsky would try to make him look edgier, or meaner, or more venal and materalistic, than he actually is. The truth of the matter is that making every depiction of the man into a hagiography is just as much of a lie, if not more of one. My experience of the guy was that he had a deeply sour personality and a petty streak that was deeply unbecoming in a wealthy, famous man in middle age. Is that a saint? No, because there’s no such thing as a saint. He was just a guy.