Red Team

In the course of my recent researches, I’ve come across a term that I rather like: red teaming. It refers to a practice in US wargames and intelligence, whereby a group of experts and spies will be broken into a blue team and a red team, with the blue team taking on the role of the US military and apparatuses of state, and the red team takes on the role of the enemy. Some of this is about trying to estimate enemy tactics, but its most vital function, from what I’ve read, is to highlight flaws in your own. Red teamers have to be creative thinkers, highly knowledgable, and willing to detach themselves from classic my-side biases they usually operate under. Most of the greatest intelligence failures in US history — notably 9/11 and Pearl Harbor — were, in some sense, a failure of red teaming: we didn’t know where the weaknesses in our defenses were, or inasmuch as we did we weren’t worrying about them.*

*Another classic red team activity is that of the white hat hacker, who breaks through the defenses of a company or government department in an attempt to highlight their weaknesses. At the beginning of the Robert Redford classic Sneakers, Redford’s ragtag crew of techies are performing this kind of function for banks.

This term spoke to me because — if you’ll forgive the impertinence — I sometimes think I’m a born red-teamer, which can be frustrating in an age of curated information silos, unchecked motivated reasoning, and rampant confirmation bias. I’ve long thought of this as a form of contrarianism, though it’s really not that: I hold fairly standard lefty views on things like the welfare state, social justice, and the value of a polyethnic, polyphonous society. It’s that my instinct, when presented with people I agree with, is to ferret out the hypocrisies and weaknesses of their arguments — arguments which are, after all, often my own arguments. I realize that this might sound like a kind of bragging, and maybe it is; but in reality, this is not something I did, exactly. It’s just a habit of mind. I could spend a lot of time analyzing where it came from, psychologically, but it’s not that interesting, even to me. Suffice it to say that my brothers are both natural red-teamers, too, so it probably comes from our childhood and/or genetics, somehow.

Maybe this is just self-flattery, but I’ve come to believe that a lack of red-teaming is really plaguing liberal (or progressive, ugh, what a shitty word) thought these days. Everybody from the campus speech police to the activist base of the Democratic Party is suffering from a problem where their ideas aren’t trouble-shot by smart people; in an environment where political ideas have become conflated with cultural identities, it seems to me that it’s really hard to have the kind of cross-political discussion that results in understanding where your arguments fall apart. This leads to an assumption that our ideas are inevitable, or obvious, or incontrovertible. (And before you get on the they’re-worse-than-us-about-this horse, I’m sure the right has this problem, too. But I’m not a conservative red-teamer, I’m a liberal red-teamer, so I don’t care about that.) It feeds self-righteousness, and I honestly think it’s part of the vicious cycle whereby politics and identity became conflated in the first place.

Let’s take, for example, the concept of privilege. I’m not going to sit here and tell you that the variety of behaviors, incentives, and cultural forces that currently go by the name of privilege on the left, and in academia, don’t exist; that strikes me as patently absurd. Of course they do. The problem is that the term privilege is completely destructive. The word was loaded long before it became a byword of the social justice movement; being told that you were privileged was tantamount to being told that you were weak, you had never earned a thing, that you were, in short, the bad guy in the story. That was before it got larded up with a bunch of complex stuff about race and gender. The word is judgmental; the word is mean. It makes people feel attacked. And that’s why going on and on about privilege is of extremely little value.

I can just hear your voice, dear blue-teamer, as you groan. I understand that instinct. There’s some blend of I don’t really care about hurting a bunch of white people’s feelings and Of course you think that, you’re a white dude in there. I’m not here to plead for the left to be nicer to white men, or at least not chiefly. I’m here to ask you what the term privilege achieves. Because I would posit that what it very distinctly does not achieve is an erosion of privilege, or the conversion of the privileged to liberal ideals. Instead, it (A) increases factionalism, and (B) alienates those who could be allies. This is about what it does in the mind of the person who wields the term, as well as the mind of the person at whom it is wielded.

As a for-instance, think about the reaction among some people on the left to the tragic case of Otto Warmbier, the American college student who was detained in North Korea, and recently died shortly after being released from that nation’s custody. Inasmuch as people were paying attention (I’ll confess that I wasn’t, really, and wouldn’t have been able to remember his name until he was released last week), most people expressed shock, and horror, along with incredulity about the North Korean government’s explanation for why Warmbier was detained (that he had stolen a government propaganda poster). But there was a distinct strain of thought among the insufferably woke segment of the left that basically said this: Warmbier’s white male privilege had led him to believe he could get away with anything, and this was his just deserts. (See Alyssa Rosenberg’s roundupfor a decent compendium of a few of those reactions. And before you start attacking Rosenberg’s politics, dear blue-teamer, remember that she was an early product of that notorious incubator of reactionary politics known as . . . ThinkProgress.) This is the use of the privilege frame to reinforce the ugly politics of identity and difference. People who gloried in Warmbier’s arrest and sentence could not have known much more about him than that he was white, male, American, a member of a fraternity, and a student at the University of Virginia — one of America’s best public universities, no doubt, but also a classic stronghold of segregation and patriarchy. But to weaponize the idea of privilege in this way is, in fact, unfair, stupid, destructive, and ugly. Whether or not Warmbier was a member of a fraternity at a conservative school, the truth is that the only thing that matters is that he’s a person, and whether or not it was his privilege that caused him to feel empowered to pull down a poster (and I’d argue that [A] we have no idea if he actually did that, and [B] teenagers of all races and genders are prone to doing things like that), it is unacceptable to dehumanize him using the privilege frame. And yet this kind of of thing happens a lot. It’s rarely this egregious, but because privilege is a word that was so loaded to begin with, it often ends up as a tool of dehumanization.

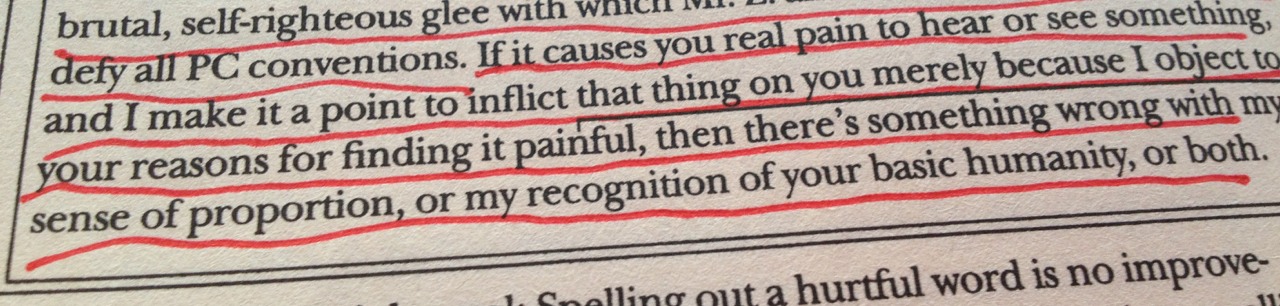

The other idea is a little squidgier, and if your instinctive feeling is that you don’t care about offending a few white dudes, then you won’t cotton to it. But as a member of the red team, I have to tell you that there are a lot of intelligent people who could be made into allies, except for the fact that they feel attacked, and ultimately alienated, when the word privilege starts getting thrown around. The word feels like an attack. Hell, the word often is an attack, dressed in a posture of defense. And there are (at least) two things to be remembered here: (1) that human behavior is ruled by cognitive experience, not objective fact, and so if someone is told they’re privileged when they feel like they’re they’re the opposite, they’re almost certainly going to react with hostility; and (2) that, shifting demographics aside, there are an awful lot of white men in this country, and if you call yourself progressive, ie, what you seek is progress, you will get farther by describing the truths behind the concept of privilege without making white men feel under siege. I’m not trying to blackmail anyone into conceding to the will of the majority, or the historically powerful; I’m not asking people to kowtow to historical elites — I’m asking people to think about gains and losses, allies and enemies, and basic humanity. You should not willfully make enemies of those who might be allies. To do so by swinging around the club of privilege willy-nilly is just dumb. Sorry, blue team. This is one of your weaknesses.

Anyway, I hope you see what I’m saying. I am in no way contending that men, or white people, have not been systematically advantaged by cultural, social, and legal forces, more or less since the founding of the republic. I’m not here to tell you that affirmative action is evil or that we should stop putting people of color in action movies or positions of power or any of that stuff. I’m red-teaming this idea. I’m trying to see where its weak spots are, so we can make our arguments better.

There are a lot of ideas on the left that could use a little constructive red-teaming, by the way. I hadn’t actually intended to make this whole post about privilege, as a term, but as usual I got away from myself. I’d say that the idea that mounting more “progressive” candidates in house races, as a way to appeal to “the base”, is the way forward for Congressional Democrats, isdefinitely one of them. A nationwide $15 minimum wage is another. Allergy to globalism and free trade is yet another. The assumption that the implementation of a social welfare state would be win-win, if only we could get greedy Republicans to leave office. That the white working class is the key to the future of the Democratic Party. (That one, in particular, strikes me as not only deserving of a little red-teaming, but of total destruction.) The list goes on.

Ugh. Now I’m tired. I wrote this whole thing in less than an hour. ZZZzzzzzzZZZzzzzzz . . . sorry. I don’t have the energy for an artful conclusion.